Caroline Brewer is a children’s author and literacy activist, a reading coach, former classroom teacher and former Pulitzer Prize jurist and nominated journalist. She has just published her debut children's novel in verse, Darius Daniels: Game On. Long-established, award-winning, and rising authors, poets, historians, children’s authors, and journalists, plus a continental breakfast and book-signing afterwards – all on the menu for the 2nd Annual Black Authors Breakfast Party and African American Read-In. It’s all happening this Friday, February 7 from 7:00 – 9:00 am in downtown Washington, DC. (1101 New York Ave NW). I am the grateful founder and organizer inviting everyone in the vicinity to join us in person or to watch the C-SPAN BookTV broadcast to be announced later this month. RSVPs requested to our gracious partner and host, Signal Financial Credit Union at [email protected]  D.C.’s Legendary Poet E. Ethelbert Miller will be our keynote reader and speaker, joined by ten other D.C.-based writers. And I’m excited to offer a “book-tasting” of my debut verse children’s novel, Darius Daniels: Game On!, which will include accompaniment by creative vocalists and musicians. Some might wonder why it’s important to celebrate black authors. It’s important because even in 2020, black authors are still rarely seen. The average person has difficulty naming more than a few black authors, teachers still tell us they struggle to find works for students by black authors, and bookstores and many libraries showcase limited titles by black authors. When we read a book, recite a poem, tell a story, or sing a song by a black writer, or listen as they read, sing, or talk to us, we bind ourselves to that person and to that work. We announce community when we bind ourselves to that person and to that work. And in the binding, we create something new and remarkable. We celebrate black authors because we want them to know that in keeping with the Zulu greeting, Sawubona, we see them. To see black authors is to laugh with them, cry with them, go deep into history, family, religion, culture, love, and friendship with them. We celebrate black authors to honor the legacy of the founder of the African-American Read-In, Dr. Jerrie Cobb Scott, who passed away in 2017. “It’s important for all of us to see ourselves in books,” Professor Scott said, and for there to be witnesses. She proposed the event to the Black Caucus of National Council of Teachers of English (of which she was a member and so am I) so that people of all backgrounds could become part of the world of stories that black writers create. From the beginning in 1990, the Read-In was her invitation for people to gather anywhere, in schools, libraries, bookstores, cafés, prisons, workplaces, and even their living rooms, to read books by African-American authors, and report those results. They went from 5,000 to a million readers within five years. So, today, I invite you to celebrate the now global phenomenon of the African-American Read-In, on its 30th anniversary, anywhere you are. I invite you to help us make sure more authors are seen and more people are witnesses. Details and RSVP at this link. Follow @brewercaroline @signalFCU on Twitter for news and updates about the Black Authors Breakfast Party and African American Read-In. Author Eloise Greenfield at the 2019 African American Read-in.

The inaugural Black Authors Breakfast Party/African American Read-In (BABP/AARI) was held Friday, February 1, 2019, and was aired in its entirety later in the month by C-SPAN’s BookTV. Learn more here about that event and other Read-Ins held in 2019. See BookTV video of the 2019 event here and a 3-minute highlight video here.

0 Comments

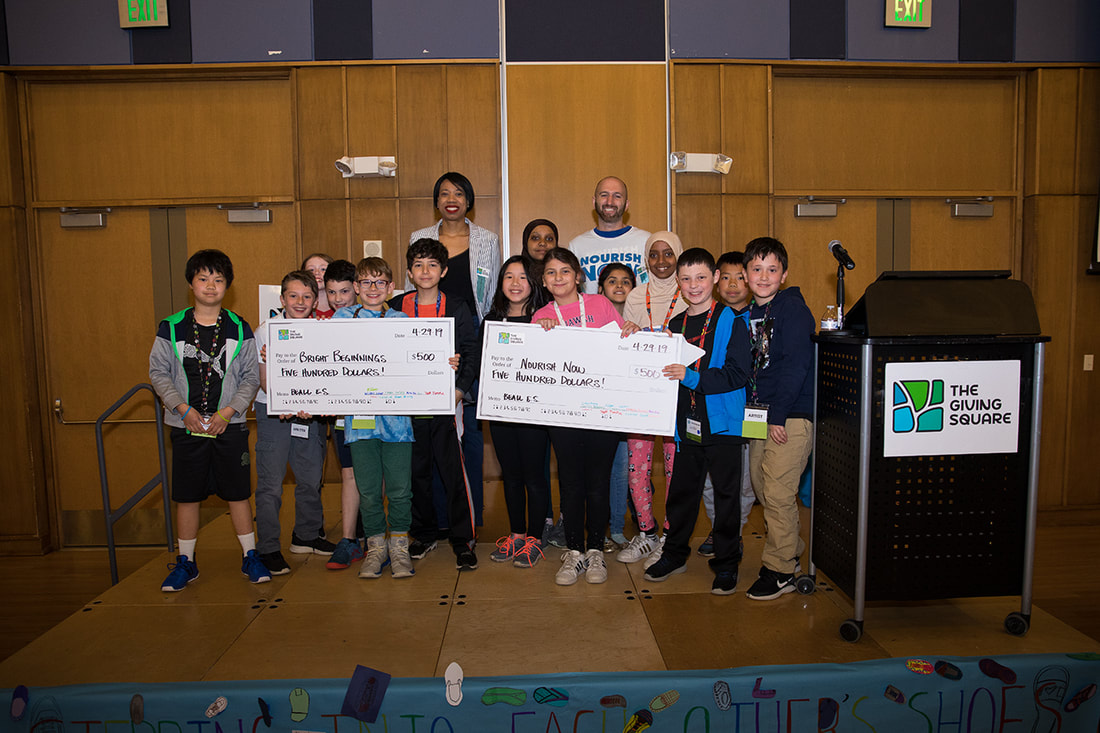

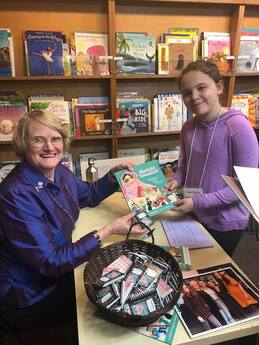

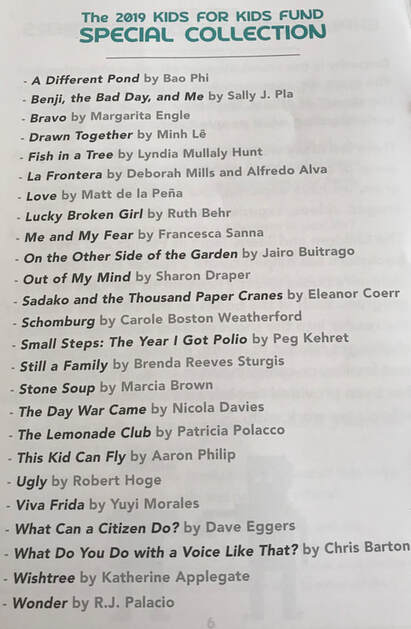

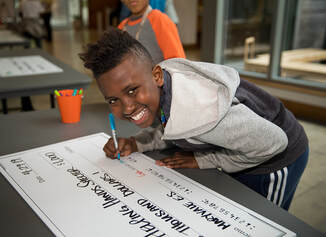

Guest blog by Katherine Marsh Katherine Marsh is the author of the award-winning middle-grade novel NOWHERE BOY. She joined with four other authors on a panel at the recent National Council of Teachers of English to talk about five book that can teach kids to change the world. I'm delighted she agreed to share them with you here. In 2015, my family and I moved from Washington, D.C., to Brussels, Belgium, for my husband’s job. I wasn’t planning to write another children’s book; my only plan was to help my children transition into a French-speaking Belgian school—a stressful full-immersion experience. But one day, while they were off at the ironically named Ecole du Bonheur (or School of Happiness), I was poking around the basement when I found a tiny door with a skeleton key. What children’s book author isn’t going to follow her curiosity and open that? What I found was a sub-basement and far in the back, a wine cellar. It was the perfect place for a boy to hide. Hiding had been on my mind ever since I’d learned that a Belgian family on our block had hidden a Jewish teenager in their house during the Nazi Occupation. This teenager had been a German refugee and refugees were on my mind, too. The year we arrived, 2015, was the height of the European Refugee Crisis; over a million refugees were pouring into Europe, including many unaccompanied minors, or children traveling alone. Sometimes, as an author, you don’t choose your story--your story chooses you. By the end of that year, I knew I had to write my middle-grade novel Nowhere Boy, the intersecting tale of Max, a hapless American boy dragged unwilling to Brussels, and Ahmed, an unaccompanied minor from Syria who finds himself stranded alone in Belgium. In 2018, Nowhere Boy was published to rave reviews and even won some awards (including the Middle East Book Award). Best of all, I started hearing from kids and classes who had been inspired by Max and Ahmed’s story to reach out to new arrivals and to start coat drives and fundraisers for refugees. This year, when I learned that the National Council of Teachers of English (NCTE) conference theme was “spirited inquiry,” I was eager to connect this to my book’s heart: How to inspire kids to expand their empathetic horizons and get involved in making the world a better place. Luckily, I wasn’t the only one. In a panel entitled, From Curiosity to Civic Engagement: Using Literature to Create Social Comprehension and Changemakers, I was joined by four fellow authors whose books not only educate kids on a variety of important topics but inspire them to get involved. In all these books, curiosity leads to a deeper understanding of the world and a clarion call to change it. As our educator-moderator Sara K. Ahmed, author of Being the Change, explained, teachers need books like these to serve as “entry points for social justice.”  In Magic Ramen, the Story of Momofuku Ando, Andrea Wang tells the story of the inventor of instant ramen, a food that saved post-war Japan from starvation and that has become a nourishing, low-cost staple around the world. Wang’s book is an entry point into classroom discussion about food insecurity, which affects millions around the globe, including many American children. Wang’s book—and resources for teachers--inspire young readers to identify problems in their own community and how they would solve them, as well as to create food drives and community pantries. Preschool-Grade 3  In Another Kind of Hurricane, Tamara Ellis Smith tells the intersecting story of two boys, one in Vermont struggling with the death of a friend, the other in New Orleans struggling with the loss of his home in Hurricane Katrina. Smith herself donated clothes to Katrina victims and was inspired to write the book by her young son’s question of who would get his jeans. The book is an entry point into the impact of natural disasters and climate change. To get kids involved, Smith created the Blue Jean Project, an initiative in which one school donates jeans to another school affected by a natural disaster. Middle Grade  In Tree of Dreams, Laura Resau tells the story of a girl with a family chocolate shop in Colorado who travels to the Ecuadorian Amazon where cocoa beans are grown to learn about an indigenous community whose home and forest are imperiled by oil exploration. Inspired by Resau’s own travels and friendships in the Amazon, the book is an entry point into environmental destruction, particularly its impact on the poor and disenfranchised. Resau, whose website includes numerous resources to use with children, encourages students to “grow their hearts” by giving them an anatomical heart print-out whose four chambers they fill with the top things they care about and that they are encouraged to add to throughout the year. Middle Grade  In Fault Lines In the Constitution: The Framers, Their Fights and the Flaws that Affect Us Today, Cynthia Levinson and her husband Sanford Levinson, a professor of law, explore twenty “fault lines,” highly debated sections of the Constitution that still impact what we squabble over today. Levinson’s book allows kids to explore contentious topics such as immigration and impeachment by focusing on the structures of government rather than by making these arguments personal. The Levinsons’ book is meant to inspire civic engagement, including a focus on speaking up and voting, and the couple’s blog regularly updates their material. Middle to Upper Grade Please feel free to use the comments section to add other books or resources for children and young adults that help teach kids - and grown-ups! - how to change the world. Here are a few more helpful organizations and links: Why Children Have Such Powerful Moral Authority, Washington Post Youth Activism Project Girls Gone Activist: How to Change the World Through Education Teaching for Change Unity Productions Foundation I'm Your Neighbor Books  Adam regularly gives food to a food bank. Odean listens to people to show he cares. These two boys attend elementary schools in Montgomery County, Maryland, where they are members of The Giving Square and identify themselves as philanthropists. The founder of this non-profit organization, Amy Neugebauer, believes “we all have something that we can uniquely contribute to the world around us.” Neugebauer and other parents decided to “engage children in philanthropy by starting a program grounded in empathetic connections to the needs of others.” The Giving Square's signature program - Kids for Kids Fund - started in 2017 at Wood Acres Elementary School, spread to four schools in 2018 and now includes 10 schools in Montgomery and Anne Arundel Counties in Maryland and Elgin, Illinois.  Neugebauer and fifth grader Anna Murray from Wood Acres helped launch Malala Yousafzai: Warrior with Words this spring at Politics and Prose as shining examples of Malala’s insistence that “one child, one teacher, one pen, and one book can change the world.”  Teachers and counselors at each school promote voluntary participation in the Kids for Kids Fund. Altogether there are 225 third to fifth graders meeting once a week for two months. Each 35-minute session occurs during recess. “Part of the message,” notes Neugebauer, “is that kids are giving up something to participate.” Children start by discussing what all kids need: “a home, shelter, food, friends, family and definitely love,” says one young girl. Education and health insurance were also on the list, “in case somebody breaks an arm.” Youngsters learn about stepping into the shoes of others using videos, activities and a collection of books curated by the partner bookstore Politics and Prose in Washington, D.C. The books may be taken home from the school library and often help start conversations at home. Children even become change agents influencing family discussions about giving.  In order to participate in The Giving Square, schools must contribute $750 for administrative costs, enlist a donor or foundation to provide $1000 for students to donate and a teacher or counselor who champions the program in the school. Toward the end of the sessions, kids begin talking about local solutions to the problems they’ve learned about, drawn from charities in the Greater Washington Catalogue for Philanthropy. During the next to last session – March Madness - each child nominates an organization. Following a lively debate, students vote and decide where to donate their $1000. In the last session, the newly energized philanthropists write their own giving pledges: “I am good at speaking and I can make useful items.” “I will be kind to people who do not have friends or have someone to play with.” “I can help because I am good at solving problems.” “I am a philanthropist.” When The Giving Square was brought to a Title I school, where most students come from families with lower incomes, Neugebauer realized “there is a universal desire to help. Everyone feels there are people less advantaged than they are. Everyone feels they have blessings in their lives.” When asked to describe their personal experiences with helping others, children in these schools said, “I taught my brother how to read.” “I helped an old lady carry her tomatoes.” “I sit with my mom when she is sad.” The meaning of philanthropy for children is giving of yourself in any way you can. And really good philanthropy, adds Neugebauer, comes with understanding the full story of someone else.  ·At a grand celebration this spring, giant $1000 checks were presented to the winning charities. Hundreds of kids were excited about philanthropy – and able to pronounce the word! The 2019 grantees include:

For more information about The Giving Square, contact [email protected].

By Karen Leggett

Sen. Dianne Feinstein (D-Calif.) met with constituents in her office recently, but it was far from a routine visit with voters. In fact, the constituents were mostly nonvoters — children in third grade to high school who were mobilized by the Sunrise Movement. They carried a large handwritten letter asking the senator to vote “yes” on a resolution favoring the Green New Deal, a plan to address climate change with economic stimulus programs. Read more of my article in the Washington Post, March 1, 2019, here. By Pamela Ehrenberg

In late 2016, the demolition trucks arrived at the library in our Cleveland Park neighborhood of Washington, D.C., clearing the way for the new building to come. It was the best possible reason to demolish a library. And the new branch will be terrific in two years. But in the meantime, every car ride to the interim location made me miss walking to our neighborhood branch even more. I needed a solution that focused on moving forward. Around the same time, national conversations were unfolding about how communities could break down barriers and talk to one another. Our country needed solutions that focused on moving forward I asked my kids (12-1/2-year-old daughter and 9-year-old son): what if we try to visit all of the other DC Public Library branches before our neighborhood library re-opens? It’s not that people from our Upper Northwest neighborhood never venture east of Rock Creek Park, or the Anacostia River. But too often it’s in a spirit of well-meaning temporary helpfulness that doesn’t generate long-term solutions. Our library visits wouldn’t focus on solutions: there’s too much foundational work to do first. Our visits are a reminder that every single community is built on strengths—and that many of us don’t yet know enough to be truly helpful. What better place than a library to remember how much there is to learn? With Metro cards and GPS, a library map and open minds, we began exploring our city. Libraries provided the excuse we needed to visit the Anacostia Museum, Labyrinth Games, the DC State Fair. The Benning branch was sort of on the way to visit grandparents in Baltimore. At some branches, we didn’t have as many hours I would have liked for a full neighborhood exploration, but I’ve learned not to postpone this sort of purposeful wandering until some mythical “free time.” Our time is now. In every community, we can find a novel to absorb on the Metro, a collection of new chess strategies, a gripping middle-grade book to enjoy together on CD. At the branches named in their honor, we’ve learned about the contributions Watha T. Daniel and Dorothy I. Height made to our city. And we’ve been able to imagine, just for a moment, living in other communities. We’ve remembered that real live people live in all four wards, even tiny Southwest, where some of the tweens play computer games at the library Saturday afternoons. Real live people approach their libraries by car and on foot, alone and in pairs, and most of them are very happy to take our photo in front of the library sign. Real live people live close to and far from public transportation, supermarkets, the array of job opportunities that people in other parts of the country may think of when they hear “Washington.” But everyone we’ve met in libraries can access . . . libraries. Meanwhile, the progress on our neighborhood branch reminds us of our deadline. I know I’ll miss this project after the last map pin is in place and our goal is eventually achieved. But I’ll also look to new goals—building on this initial comfort level toward deeper conversations about our shared city. Because library locations aren’t acorns but “branches:” not a finite ending but a path to what’s next. And for our family, the exploration is just beginning. |

Karen Leggett AbourayaArchives

April 2024

Categories |

BOOKS |

RESOURCES |

© COPYRIGHT 2020. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

|